Biology Majors Contribute to National Research Database in Class

A new option in the biology degree program introduces majors to research and lab experiences at the start of college careers.

A new option in the biology degree program introduces majors to research and lab experiences at the start of college careers.

Saint Leo University has become one of approximately 100 colleges across the country to offer two semesters of coursework in thebiology majorthat puts students to work almost immediately in collecting viruses for a growing research database. The development is yielding multiple benefits. Students value having the chance as freshmen or sophomores to experience scientific discovery through a hands-on project, and they are making contributions to a huge repository of information that is valuable to other scientists near and far.

Saint Leo University has become one of approximately 100 colleges across the country to offer two semesters of coursework in thebiology majorthat puts students to work almost immediately in collecting viruses for a growing research database. The development is yielding multiple benefits. Students value having the chance as freshmen or sophomores to experience scientific discovery through a hands-on project, and they are making contributions to a huge repository of information that is valuable to other scientists near and far.

The addition of the courses also highlights Saint Leo's identity as a teaching university. Faculty are constantly look for ways to help students better engage with the topics they are studying.

The biology major happens to be one of the most popular majors at the College of Arts and Sciences and is offered at University Campus.

Improving Science Education

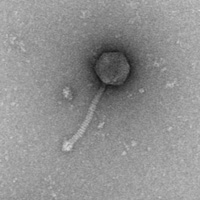

Science faculty have been attuned to the progress of the 11 students who just completed the first semester of the three-credit lab course called Intro to Research - Phages Hunters. A phage (rhymes with "sage" and pronounced with the "f" sound at the beginning) is a virus that not only infects bacteria, it changes the bacteria it attacks.

Some phages can cause benign bacteria to become pathogenic (disease-producing) by transferring in pathogenic genes; some can just use the bacteria as a host to make more viruses before killing them, explained Dr. Iain Duffy, a faculty microbiologist who teaches the class, along with laboratory manager and instructor John Duncan. Consequently, understanding how these bacteriophages behave can be medically useful: bacteriophages can sometimes be harnessed to kill off bacteria that make people sick, sometimes terribly sick. This program can advance that possibility by increasing the knowledge of the genetics and life cycle of bacteriophage.

Some phages can cause benign bacteria to become pathogenic (disease-producing) by transferring in pathogenic genes; some can just use the bacteria as a host to make more viruses before killing them, explained Dr. Iain Duffy, a faculty microbiologist who teaches the class, along with laboratory manager and instructor John Duncan. Consequently, understanding how these bacteriophages behave can be medically useful: bacteriophages can sometimes be harnessed to kill off bacteria that make people sick, sometimes terribly sick. This program can advance that possibility by increasing the knowledge of the genetics and life cycle of bacteriophage.

The study of phages for such purposes is not a brand-new idea, though. It actually began about 100 years ago, but was eclipsed for decades by the development of antibiotics. But now, scientists and doctors need tools that can work in instances where antibiotics fail, so broad study of phages has resumed.

The study of phages for such purposes is not a brand-new idea, though. It actually began about 100 years ago, but was eclipsed for decades by the development of antibiotics. But now, scientists and doctors need tools that can work in instances where antibiotics fail, so broad study of phages has resumed.

This area of research is a massive undertaking. Phages are numerous and exist everywhere, but are invisible to the naked eye, so they have to be collected and identified by many, many trained individuals.

The collection step is where college students can be helpful. The prestigious nonprofit Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and itsScience Education Alliancebegan bringing colleges into developing corps of phage hunters in 2008 with a two-semester course curriculum. Participating institutions such as Saint Leo use the course, and eventually submit selected phages samples (they need certain characteristics to make advanced study possible) for inclusion in the program's central research database, which is housed at the University of Pittsburgh.

Student Contributions Start at the Ground Level

The search for phages by Saint Leo students literally began with small scoops of the Florida campus or from the yards of their homes. Students followed designated procedures to extract soil samples and brought them back to the lab. Then they learned what microbiology lab techniques to apply to look for the phages in the sample. They identified phages and even named them. In all, 14 phages were collected. It is labor intensive work in the lab for the students, so the class has the assistance of David Guadarrama, a senior in the program, and another student lab assistant, senior Kaylee Martin, who helps Duncan with the preparatory work that needs to be done in advance of class sessions.

The search for phages by Saint Leo students literally began with small scoops of the Florida campus or from the yards of their homes. Students followed designated procedures to extract soil samples and brought them back to the lab. Then they learned what microbiology lab techniques to apply to look for the phages in the sample. They identified phages and even named them. In all, 14 phages were collected. It is labor intensive work in the lab for the students, so the class has the assistance of David Guadarrama, a senior in the program, and another student lab assistant, senior Kaylee Martin, who helps Duncan with the preparatory work that needs to be done in advance of class sessions.

Throughout this process, the students also gained practice in safety procedures, problem solving, record keeping, evaluating data, and designing and interpreting experiments. Eventually, the students reached the point of seeing a visual representation of the genetic markers of some of the phages.

I enrolled in this phage class because I love research, and I have a passion for science," said Rebekah Wachob. She has had lots of fun, she said, and it has kept her busy. Students seem to talk about the course steadily even outside of class, Duffy has observed.

The excitement the course generates among young students is helpful with another widespread dilemma facing the country: we need more scientists. To accomplish that, colleges and universities need to keep the interest of more talented students who switch from science to other majors before they develop an attachment to the field. HHMI, which is based in Maryland, developed this course to give students nationwide a taste of hands-on research early on, and to let them feel a connection to real research. There is already some evidence (from the first five years of the network) that this model helps students to think about themselves from early on as scientists.

The excitement the course generates among young students is helpful with another widespread dilemma facing the country: we need more scientists. To accomplish that, colleges and universities need to keep the interest of more talented students who switch from science to other majors before they develop an attachment to the field. HHMI, which is based in Maryland, developed this course to give students nationwide a taste of hands-on research early on, and to let them feel a connection to real research. There is already some evidence (from the first five years of the network) that this model helps students to think about themselves from early on as scientists.

That is how Dr. Duffy refers to the students, as scientists, in class when, for instance, he showed them enlarged images of their phages taken by an electron microscope at another institution in the network. Or when he discussed the mathematical calculations they need to complete to conduct a specific experiment.

Future Research Options

Guadarrama, one of the lab assistants for the class, said he is confident the class will help the students as they proceed. "I personally wish there was a class like this when I was a freshman. It would have made me a better student and lab assistant. I was very impressed with the class overall. They did so much this semester, even though for many of them this is their first exposure to research. I believe they will be successful in their upper division classes and I'm proud to have been their lab assistant.''

Duffy has already told the Phages Hunters students about the projects that they will handle in the second semester of the course. Purified DNA from selected phages is being sent to the University of Pittsburgh, where the genetic material is sequenced. In that process, scientists examine the material and determine in what order the four basic building blocks common to all DNA occur with a particular sample. This sequence information will be returned to Saint Leo at the start of the spring semester for study in the second class, which progresses into the field of bioinformatics. Students will use software programs for this work.

Also, over the course of next semester, Duffy said the next class will aim to show that the 14 phages found are "new and novel."

Students can further use the material they are starting to develop this year for further exploration and presentation at student-level sections of scientific conferences, Duffy said. Part of the program requirements are that Saint Leo send student representatives of the class to a statewide conference in April and a national symposium in June. Other conferences beyond that are also possibilities. And any of the students could select some aspect of the work they started this year and continue with it for the research projects that will be required of them when they are seniors.

(This story uses information from "Introduction to Bacteriophages" by Stephen T. Abedon, posted September 28, 2016 on www.phage-therapy.org)