Faculty Members' Research Uncovers Site of Once-Lost Florida Town

Faculty Members' Research Uncovers Site of Once-Lost Florida Town. State-approved marker to be unveiled Saturday, November 23

Faculty Members' Research Uncovers Site of Once-Lost Florida Town. State-approved marker to be unveiled Saturday, November 23

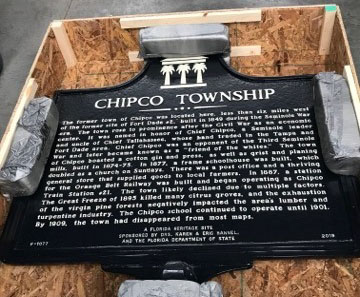

Two cultural scholars from Saint Leo University are using a Saturday during Native American Heritage Month to announce that they have been able to pinpoint the site of a once-bustling trading town whose name had been all but lost to modern times. An official Florida state marker will be unveiled November 23, on a country road a bit north of University Campus, to tell travelers about Chipco, a town named after a Seminole chief.

The town had a lumber-planing and gristmill, a school that also served as a church on Sundays, a general store, a post office, and a nearby railway link in the 1800s. Relations were cordial between the Seminole Indians and the white settlers in the area, according to Dr. Karen Hannel and Dr. Eric Hannel at Saint Leo. At its height around the 1880s, Chipco was fairly well known in the region, they said. People have no reason to know this now, though.

The town had a lumber-planing and gristmill, a school that also served as a church on Sundays, a general store, a post office, and a nearby railway link in the 1800s. Relations were cordial between the Seminole Indians and the white settlers in the area, according to Dr. Karen Hannel and Dr. Eric Hannel at Saint Leo. At its height around the 1880s, Chipco was fairly well known in the region, they said. People have no reason to know this now, though.

So the Hannels, with the agreement of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, invested in the research necessary to secure the marker and have installed it along a local Pasco County road between the two contemporary communities of Blanton and St. Joe. The marker will be unveiled on the Saturday before Thanksgiving, as November is Native American Heritage Month.

"It's an act of remembrance. This location was forgotten," said Eric Hannel, who holds a Master of Legal Studies in Indigenous People's Law from the University of Oklahoma College of Law, as well as a doctorate in the interdisciplinary study of humanities and culture, and public policy from Union Institute and University. He teaches part-time at Saint Leo, specializing in history courses. Karen Hannel, chair of the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences, and Eric sometimes research topics together. She, too, holds a doctorate in humanities and culture from Union and typically teaches fine arts history and humanities.

"It's an act of remembrance. This location was forgotten," said Eric Hannel, who holds a Master of Legal Studies in Indigenous People's Law from the University of Oklahoma College of Law, as well as a doctorate in the interdisciplinary study of humanities and culture, and public policy from Union Institute and University. He teaches part-time at Saint Leo, specializing in history courses. Karen Hannel, chair of the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences, and Eric sometimes research topics together. She, too, holds a doctorate in humanities and culture from Union and typically teaches fine arts history and humanities.

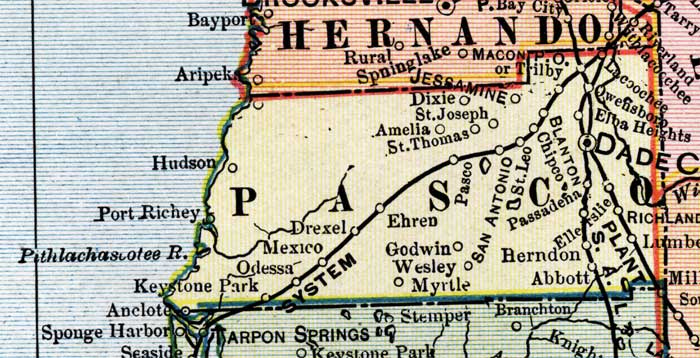

The two are hoping that as people hear of the placement of the Chipco town marker, families with descendants from the area will help by looking into items grandparents may have left behind. They are specifically interested in old newspapers, books, maps, land records, letters with postal marks and other artifacts from Chipco that could help them fill out the town's story. Such sources (along with websites) have already helped them establish the town's existence, and more would be helpful in filling in this gap in Florida history. "We'd love nineteenth-century newspapers," they said.

Discovery by chance

It is just chance that the Hannels came upon a local research topic close to their interests, especially Eric's past scholarship—his dissertation was focused on the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. The couple happened to purchase property in the area near Chipco's former location a little more than three years ago, partly for its proximity to their university jobs. They knew nothing then of the town's founding, its development, or its demise. A couple of road signs nearby for Chipco Lane and Chipco Ranch Road set them to wondering about the name's origin, and asking questions of neighboring landowners whose descendants settled into the ridge some generations back.

Chief Chipco, the namesake of the town, is known to some through history texts. He lived during broader campaigns by the American federal government and state of Florida to move or remove Indians and take over land holdings, which in this case resulted in the three Seminole Indian Wars fought in Florida. All the wars were significant to his life, the Hannels' research indicate. Chipco's father was killed during the first war, which took place from 1817-1818. He fought as a celebrated warrior in the second war (1835-1842), but the conflict was costly to both sides and fewer than 500 Seminoles remained after that conflict, according to state history sources.

When the third war (1855-1858) began, Chipco elected to keep his band out of the conflict. He was exiled by other Seminoles. White settlers began to see him as a friend, perhaps because of his neutrality. Chipco and his followers, according to local legends the Hannels have found, lived quietly near the spot the Hannels have been researching, at least for a time.

Trading post grows up

The trading post grew into a town, and was apparently named after the chief, though he spent the end of his life near Lake Pierce, FL. Settlers grew crops including squash, and some citrus and tobacco, and felled timber to move on a small railway. A planing mill was established to turn lumber into boards and a grist mill was also built, which turned grains into flour. A school was established, a postal office opened, and even a doctor lived there for a time. The accuracy of the census records from the time has not been determined, but around 1880, 50 families (not individuals) were recorded as living in Chipco.

With some map work, some luck, and the goodwill of neighboring landowners, the Hannels were able to locate by foot the probable ruins of the headwaters dam used by the mill. This would be the spot where mill owners and others would have created a dam to temporarily halt the natural flow of water from streams and lakes from the north. Their goal was to create enough pressure so that when the dam was opened and the pent-up water released, the resulting force would set into motion a huge wheel. Waterpower was harnessed to cut lumber and boards in the most efficient process available at the time. Waterpower could also be harnessed to make millstones grind crops into flour.

Images of old mills in operation are fascinating to watch, but not much is left at the Chipco mill site, the Hannels said. A casual observer would not be able to recognize the original function of the remaining brick wall parts, Karen Hannel said. Still, finding it helped them deduce where other important community spots would have stood, explained Eric Hannel. "The mill would have been at the south end of town, not too far from the train depot."

Bad economic times

There are some chapters from Florida history that would have affected Chipco, Eric Hannel noted. In the winter of 1894-1895 there were freezes in December and again, more severely in February. The harm to crops and citrus trees was devastating to the communities' economy. Residents of a community of freed African-Americans not far from Chipco—Freedtown—lost their crops and moved to other towns, for instance, Florida history records and a local marker note. The Hannels have not found specific verified accounts about the Great Freeze draining population away from Chipco, but consider it likely.

Another blow followed when Chipco's railway fell behind, technologically. Chipco had one of the narrow railway beds of the time used for places with smaller cargo loads. To the south, in Dade City, wider tracks were laid to accommodate larger trains, cars, loads, and generally more trade.

In 1903, Eric Hannel found, the Chipco schoolhouse was closed. The drop in the number of schoolchildren could not have been considered temporary, because the material used to construct the school was "sold board by board," leaving no structure behind for any future resurgence, or historical reminders. That makes sense, Eric Hannel said: "It was probably less wasteful because it took so much to resource that material. I would imagine you wouldn't let good things go to waste."

In 1903, Eric Hannel found, the Chipco schoolhouse was closed. The drop in the number of schoolchildren could not have been considered temporary, because the material used to construct the school was "sold board by board," leaving no structure behind for any future resurgence, or historical reminders. That makes sense, Eric Hannel said: "It was probably less wasteful because it took so much to resource that material. I would imagine you wouldn't let good things go to waste."

Finally, he said, "By 1909 Chipco had disappeared off the map."

But not from history. The Hannels have written an article on their research they hope to see published in an academic journey, and have a presentation they developed for community groups.

Anyone with more information to contribute, or anyone who wants to attend the Chipco historical marker dedication at 11 a.m., Saturday, November 23, should contact Karen Hannel for information. She can be reached at Karen.hannel@saintleo.edu.