101-year-old ‘Buffalo Soldier’ Shares Stories Of Valor, Resilience With Saint Leo University And Community

Sociology Research Symposium welcomes the Army veteran to share ‘living history’

Sociology Research Symposium welcomes the Army veteran to share ‘living history’

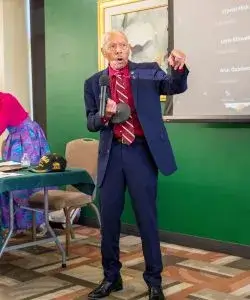

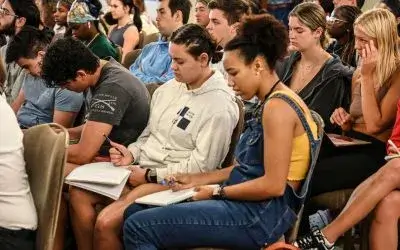

At 101, U.S. Army veteran Roy Caldwood could sit back, rest and relax, but on October 26, he spoke at Saint Leo University’s Sociology Research Symposium before a standing-room only crowd of students, employees, and members of the public. Nearly 50 people also joined via Zoom to hear Caldwood’s stories of valor and resilience during World War II and later as a corrections officer at Rikers Island in New York.

Caldwood served in Italy during World War II as part of the renowned Buffalo Soldiers, the 92nd Infantry Division of the U.S. Army, named after the 19th century African American cavalrymen. He holds the esteemed title of being the last known Buffalo Soldier in the state of Florida, recognized by the National Buffalo Soldier organization.

This event was sponsored by the university’s Department of Social Sciences, the College of Arts, Sciences, and Allied Services, Office of Military Affairs and Services, the Caribbean Students’ Association, and Alpha Kappa Delta International Sociology Honor Society. Vice President of Academic Affairs Susan Kinsella noted that several sociology students and other students would be conducting research based on the event, and instead of just reading about history, they would get to hear from the person who lived it.

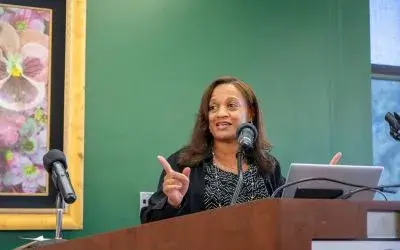

Dr. Janis Prince, associate professor of sociology and chair of the Department of Social Sciences, served as moderator for the event and interviewed Caldwood.

He started off with a story about the racism he encountered while serving in Virginia and attending a movie. Soldiers armed with bayonets made him and other African American soldiers move from seats that were “whites only,” saying “you can’t sit there,” Caldwood said.

Dr. Heather Parker, dean of the College of Arts, Sciences, and Allied Services and a history professor, noted that African American servicemen such as Caldwood left northern cities like New York where African Americans had more equality, to train in the South. “This was a sacrifice,” she said. “They were brought into the armed forces and the message was clear — you are not good enough to serve alongside white servicemen.

“They were placed in segregated units and segregated barracks and segregated everything,” she continued. Northern African Americans were used to prejudice and inequality, but they were not accustomed to the overt and hostile hatred, discrimination, and segregation to which they were exposed in the South.

Seeing an advertisement in the military publication Stars and Stripes that said Black men were needed to join the Buffalo Soldiers, Caldwood quickly signed up to become a member, hoping to escape the treatment he received in Virginia.

“The Buffalos were guys being trained to be real soldiers,” he said. “Just the thought of being a Buffalo was exciting.”

Prince asked him to describe his early days in training camp preparing to be a Buffalo Soldier.

“I trained in Arizona at Fort Huachuca,” Caldwood said. “Getting there was a journey. We took the train. People like me [Blacks], you had special cars to sit in. Ours were right next to the smoke-filled engine. Smoke was pouring in. We looked like lumps of coal. But we didn’t care. We knew we were going to have a much better life.”

Since Caldwood had been on a pre-medicine track at Saint John’s University in Minnesota, he became a medic and was assigned to a reconnaissance unit. He admitted to being somewhat afraid of heights, but “I was up in the mountains” of Italy, he shared. “Those days, you walked up the mountains and used mules. I went up with the mule train.”

“Can you tell us about ‘Purple Heart Stretch’ road?” Prince asked. This was an area of Italy in which the Germans were hiding in the mountains. “So one particular batch [of German soldiers] who we were assigned to keep track of, they found what they thought was an ideal spot where they could fight until they died and kill as many of the enemy as they could,” Caldwood recalled. “They killed so many that we gave it a name, Purple Heart Stretch Road.”

He told the story of a humanitarian effort conducted to obtain food for those in a village near the road. “They needed the food, etc., so I suggested what if I and two other soldiers escort the women to the [nearby] town,” he said. “I spoke the most Italian.”

The trip was OK’d by a superior officer. “I let the women lead the way as they knew the roads and everything,” Caldwood said. “Boy was I sorry. When I looked at where the hell we were walking, I almost had a heart attack. Purple Heart Stretch, and the Germans were looking down on us, ready to shoot and kill. You can’t panic; you can’t walk off. They were looking at us. We made it through the town. The shops had nothing. So we headed back.”

They were halfway back to the village when a mortar dropped and the small group hit the ground. “They generally don’t miss,” Caldwood said. “I raised up my head and saw a partial wall. I got up, called to the group, and said, ‘to the wall, to the wall.’ We got behind the wall, and then they really fired. About 20 or 30 mortars. The women were praying. I started to say to the girls, ‘it’s not working; maybe we should do something else.’ Then I listened to the mortars. [He realized] They’re not trying to kill us. They’re tell us something. They saw us when we first stopped on the ground there. They checked things out and learned we were on a humanitarian mission.”

Instead of killing the Americans and Italian women, they said they would peacefully surrender to Caldwood’s platoon. “I stood out in the sun where they could see me,” he said. “They didn’t kill me. I called to the group, ‘let’s go.’ And about a couple hours later, they did peacefully surrender to our platoon.”

The Buffalo Soldiers as well as other American military personnel were welcomed throughout Italy and hailed as heroes. They were not looked down upon or treated poorly, Caldwood said.

“I told the Germans that they would go to the states and be accepted,” he said. “I will go to the United States, and being Black, I will not be accepted.”

Criminal Justice Leader

Prince asked Caldwood, “How did your time in the Army help you become the person you are today?”

“I am a rule-breaker,” he replied. “I look to see how to help a situation.”

Once again heeding an advertisement he saw in a newspaper, Caldwood became a corrections officer when he returned to the United States. In his time as a New York City Department of Corrections assistant deputy warden at Rikers Island, he said, “I thought all a guy needed was discipline. I found that was wrong. The first thing I did when I began being in charge of programs, I went into every cell block, and I listened to them [prisoners’ wants and needs]. There were a lot of things the warden couldn’t do, but he let me do what I could do. I gave them weddings. I had the bakery bake them wedding cakes. I had known entertainers come and put them in the auditorium for shows.”

Caldwood’s treatment of prisoners helped him to navigate and safely negotiate non-violent solutions to hostage situations at the prison, including when he was briefly taken hostage during the 1972 Rikers Island riot. He shares those stories in his book, Making the Right Moves: Rikers Island & NYC Corrections.

Not only did Caldwood earn a Bronze Star for his service in Italy, in 2001, he also was awarded the Commissioner's Award for Bravery and in 2016, he received the New York City Department of Corrections Guardian Association Medal of Honor, Valor, & Merit. In 2023, Tampa Mayor Jane Castor proclaimed April 5, 2023, as Roy Caldwood Day.

Parker, dean and historian, urged students and those attending the presentation, to recognize and appreciate that Caldwood's and other Black military personnel’s “sacrifices paved the way for the freedoms and access subsequent generations now enjoy.”

“They served with distinction — fighting for the abstract hope of a distant future where they would be treated as equals in their own country,” Parker said. When they returned home, they did not find that. “So they focused their experience of the world, their confidence, their skills and sense of self and pride on fighting to force America to live up to the promises so eloquently articulated in the Bill of Rights,” she said. “It is no accident that the modern Civil Rights Movement as we know it began in earnest upon the return of African American servicemen from service in World War II.”

Looking around the room, Parker said, “This is why you standing here are enjoying freedom.”

She told Caldwood, “I want to make sure you know and understand that we appreciate all that you sacrificed and all that you did.”

Funding for this symposium was made possible in part by a Sociological Research Grant from Alpha Kappa Delta International Sociology Honor Society.

View the recording here.